- Home

- Paul Bernardi

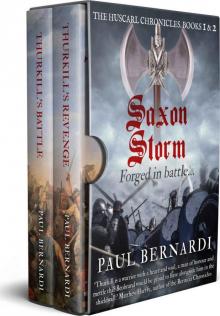

Saxon Storm: The Huscarl Chronicles Books 1 & 2

Saxon Storm: The Huscarl Chronicles Books 1 & 2 Read online

Saxon Storm

The Huscarl Chronicles Books 1&2

Paul Bernardi

Thurkill’s Revenge © Paul Bernardi 2018.

First published in 2018.

Thurkill’s Battle © Paul Bernardi 2019.

First published in 2019.

Paul Bernardi has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

This omnibus version first published in 2021 by Sharpe Books.

Table of Contents

Thurkill’s Revenge

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

END NOTE

Thurkill’s Battle

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY - ONE

TWENTY - TWO

TWENTY - THREE

TWENTY - FOUR

TWENTY - FIVE

TWENTY - SIX

TWENTY - SEVEN

TWENTY - EIGHT

TWENTY - NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

EPILOGUE

Historical Note

Thurkill’s Revenge

Paul Bernardi

ONE

1 September, the Great Hall, Wintanceastre

“No!” Harold’s gloved fist slammed down on the oak table around which his leading nobles were gathered. Wooden platters and cups were sent flying in all directions, clattering noisily as they hit the straw-covered stone floor. “I have made my decision and that is an end to the matter.” Harold, King of the English, glared about him, his face set like thunder, as if daring any of the assembled lords to challenge his word.

Thurkill, just seventeen summers old and a newcomer to the councils of great men, did not flinch. As an honour to his father, Scalpi, one of the King’s most trusted and loyal huscarls, he had been allowed to stand as a door warden within the king’s great hall at Wintanceastre. Normally such an honour would go to more experienced, battle-hardened warriors, and Thurkill was neither. True, he had shown great promise from an early age, displaying admirable prowess in weapons-craft under his father’s tutelage, but he remained, nonetheless, untested and unbloodied in battle. He was here simply because he was the great Scalpi’s son and the king wished to favour his thegn.

Their family had served the Godwines for several generations and their reputation was fearsome and well-deserved. Always to be found where the fighting was thickest, standing foursquare with the other huscarls; men who would surround their lord, ready to give their life in his defence if the occasion demanded. It was a life of honour and duty and Thurkill longed to add his name to those of his father, his grandfather and his father before him.

Their lord, Harold, head of the powerful Godwin family and – since the beginning of the year – king of all England – needed all the men he could find, young or old. The threat of invasion had hung over him since the very start of his short reign just eight months ago. Across the channel, Duke William of Normandy had made no secret of the fact that he intended to take the throne by force, to make good – he claimed – on a promise made to him by King Edward; a promise which Harold had supposedly endorsed not two years since.

All year, word had been reaching the English court that men were flocking to the Duke’s banner; his own retinue being swelled by hundreds of landless adventurers eager for the chance of booty in one of the wealthiest lands in Christendom.

But, as the long summer months had dragged on, no ships had been sighted along the southern coast. Day after day, the army watched and waited, expecting – at any moment – to see the horizon awash with bright sails billowing in the wind. Hopes had begun to rise that the danger had passed – at least for this year. Everyone knew that the channel between Normandy and England was best avoided in the autumn months. Storms could blow up out of nothing, blowing ships miles off course, dashing them against rocks, sending men to a watery grave. Surely, it would soon be too late for William to risk a crossing?

But, just when thoughts had turned to winter preparations, Harold’s spies had reported a great army and a huge fleet – said to be one of the greatest fleets ever seen, bigger even that the Danish invaders of old – had gathered in the harbour of St Valery, no more than a day’s sail from England. All that stood between him and the southern shores of England was a favourable wind.

To make matters worse, the fyrd - the common men of England’s towns and villages whose duty it was to provide military service to their king – was restless. It had been assembled for almost five months; more than double what was normally required. The men, thousands of them living cheek by jowl in huge camps, had been idle for weeks, with little to do other than eat, sleep and drill all day. Supplies were dwindling and men were going hungry, giving rise to the risk of thieving and murder. A few miscreants had been hanged, as an example to the rest, but discipline was wavering. And then there was the risk of disease. It was a miracle that no foul pestilence had so far swept through their ranks.

Above all, though, they yearned to be released. Those who came from the land needed to return home to help bring in the harvest. If the crops were not gathered in before they withered, it could mean death by starvation for many over the long winter months. Many more would die than from any battle. Almost daily now, groups of men would arrive at Harold’s tent, petitioning the king to be allowed to leave, but – so far – he had refused every one of them.

But many thegns were now speaking of rumours of mass desertion, of mutiny even. They knew their people; there was only so far they could be pushed and that line was fast approaching. Never afraid to listen to those below him, Harold had called today’s great council to debate the problem. It had begun calmly enough, but things were now getting out of hand with voices raised on all sides, until Harold had been forced to intervene to impose order.

The sudden outburst had shocked Thurkill, but he managed to keep his emotions in check. He had been trained to stand fast in the face of the enemy, no matter what, so the young Saxon remained stock still, as straight as the shaft of the finely crafted spear he held in his right hand. He was a tall man, standing over six feet in height and, with his helmet on, he towered over most others.

In his left hand, his fingers gripped the leather straps of his shield so hard that the whites of his knuckles showed. The shield, a circular piece of wood made from a number of planks glued together, was like a dead weight, dragging on his arm, but he dared not let it slip lest he draw attention to himself. The shame it would cause his father was unthinkable. It was covered with leather on which a design ha

d been painted around the central iron boss: the golden wyvern of Wessex standing proud on a red background. It was pristine, having – like him – never seen battle.

He longed for that day. The day when he would stand by Scalpi’s side in the shieldwall; his shield overlapping his father’s, protecting his left side, just as that of the man to his left would protect his. He had been brought up on the stories of old; stories of great battles against the Vikings, of feats of great daring and courage. Sitting by the hearth fire in his father’s hall in Haslow, he would sit, open-mouthed, as Scalpi related tale after tale until his aunt, Aga, had shooed him away to bed, his eyelids drooping as he sat. One day, he had promised himself as he lay in his bed thinking back over what he had heard, he would be a great warrior too. Like his father. One day, his name would strike fear into the hearts of his enemies on the field of battle, like Byrhtnoth at Maldon, or even Alfred himself.

Back in the present, he wished his sister, Edith, could see him. Two years younger than him, she had been left with Aga back in Haslow. She had pleaded with their father to let her go, but he had been steadfast in his resistance. Since their mother had died of the sweating sickness some years back, Scalpi had been fiercely protective of his daughter and he was not, he had yelled – his patience finally exhausted - about to let her be surrounded by so many uncouth, hairy-arsed ruffians. Edith had run sobbing from the hall and had not emerged from her room before they had left the next day. Thurkill felt the pain of separation particularly hard. He valued her above all other things and they had never been apart for so long before. Yes, they bickered and fought like any siblings, but underneath it all was a bond that was stronger than oak. For now, though, he comforted himself with the thought of how proud she would be if she were there to see him. He looked every inch the noble warrior even if he were still just a boy with only the first wisps of a moustache showing on his face.

Scolding himself for allowing his mind to wander, he tried, once again, to focus on what was being said. It was hard, though; the heat of the fire was oppressive, made worse by the smoke that clung to the walls like a winter’s fog that hugged the land. Although summer was not long passed, the weather had already become unsettled. High winds had brought thick, dark clouds laden with rain in from the east, increasing the men’s clamour to return to their farms before their crops were destroyed. Without the fire, they would have had to stand shivering in damp clothes.

As he watched, the air above the fire shimmied, making the people on the other side look, to his watery eyes, as if they were dancing. Smoke swirled around the flames, fighting to make its way up and out of the small hole in the roof above.

Under the weight of his clothes and armour, Thurkill was sweating heavily now. Most of the burden came from his byrnie. Made from small rings of iron riveted together, the mailshirt reached all the way down to his elbows and knees. It was a costly piece of equipment that only the wealthiest warriors – huscarls like him, in the service of a great lord - could afford, but it was also a lifesaver. As heavy as it was, the protection it gave from sword cuts, spear thrusts and even arrow shots, was invaluable. After long hours of use, though, wearing it could become almost intolerable, like carrying a small child for hours on end. Under it, he wore a padded, long-sleeved tunic that shielded his body from bruising or abrasions caused by blows to the mailshirt. Although the tunic made the byrnie more comfortable, it also made him incredibly hot. He could feel small rivers of sweat trickling down his back, while yet more dripped down from the helmet’s sweatband and into his eyes, stinging them until he could blink them away.

The king’s outburst had silenced the hall. Even the thralls had stopped in their tracks, midway to refilling cups or clearing platters from the tables. The only sounds were the crackling and spitting of the logs in the fire and the whining of one of the king’s dogs, woken from its dream-filled slumber in front of the hearth.

Now Harold stood with both fists pressed down on the table, his head bowed forward so that his features were obscured by his shoulder length blonde hair. It was plain to see that the pressure of the past few weeks was wearing him down. He must know that the decisions he made in the coming days could seal his fate one way or another, to say nothing of that of hundreds if not thousands of his countrymen whose lives it was his sworn duty to protect.

Eventually, Harold rubbed his hands over his face and flopped down heavily in the great oak chair that stood behind him, draped in furs. It was Gyrth Godwineson who first dared to break the silence. As the king’s brother, he – more than most – could speak plainly and honestly to the king, without fear of rebuke.

“Lord, we understand the reasons for you decision, but is it wise to let the fyrd disband at this critical moment? We may soon have dire need of them. William’s ships are gathered not far from us.”

Harold looked up at his beloved kinsman. “Dear brother, we don’t have a choice. They have been held here far longer than our laws allow. You’ve heard the mutterings as much as I have; they need to be away to their farms. Whatever else may happen, just think how much worse things will be for my people if they fail to bring in the harvest.”

Leofwine, the youngest of the three siblings, now joined the debate in support of Gyrth. But where Gyrth was measured in his words, Leofwine had ever been headstrong and impulsive. “My noble brother is right, Lord. Whilst the weather is bad now, who’s to say things won’t improve to allow the Normans to sail in a few days? With no army to protect the coast, we would be destroyed. It is folly to let the men go now; at least wait until the end of Haligmonath.”

Harold sighed impatiently as if he were having to explain things to a dim-witted child. “That would be too late, Leofwine. The harvest may well have ruined by then, especially if these storms continue. For as long as I remain king, my first duty is to care for my people and I would not have them dying of hunger this winter. I will not stand at gates of heaven with that on my conscience.”

“Lord.” Thurkill realised with a start that his father had spoken.

“Speak, Scalpi. I would have your opinion on this matter. My brothers’ brains have become clouded by this damned smoke.”

“Whether we keep the fyrd in the field or not, we cannot ignore that our supplies are dwindling. We have bled these lands dry over the last four months and we are having to forage further and further afield to find sufficient victuals. None of this comes cheap to your coffers; as the food becomes more scarce, so the price goes up. Either we must send the men home or else to move the army several days’ march from here where we might find new stocks of grain and livestock to feed our seven thousand mouths.”

Harold nodded, rubbing his stubbled chin as he considered Scalpi’s counsel. “As ever you speak wisely, my loyal thegn.”

Then rising to his feet, he continued. “My mind is made up. I would bring this council to a close as we have talked enough. The fyrd will disband one week hence. We must place our faith in God that the year is far enough advanced to deter the threat of invasion. My people shall return to their farms to gather in their crops and prepare for the winter. But we will plan ahead for the spring when, I am certain, we will feel the wrath of our Norman cousins. Until then we rest, grow strong and make ready to receive them.”

Gyrth nodded slowly in grudging acceptance of Harold’s ruling. Like most men, he knew that a royal decree once issued, must be supported. It was a lesson that Leofwine, however, was yet to learn as his youth and impetuosity combined to give vent to his feelings.

“Madness! The Normans will come and we will be defenceless. Because of you, brother, none of us will live to see the feast of our Lord’s nativity.” With that he stormed from the hall into the night, kicking over a bench on his way out.

“Leofwine!” Gyrth shouted as his back.

Harold laid a restraining hand on his brother’s arm. “Leave him be, brother. Let the night air cool his temper. He is loyal and stalwart but lacks the maturity to see the fuller picture, as I must.”

&nb

sp; “That may be, Lord, but you are too soft with him. He needs to learn respect for your position. Talking to you like that when you were Earl of Wessex would be bad, but now that you are king, he should not be seen to challenge your word in front of others.”

“I will speak to him about it tomorrow, Gyrth, but for now my bed awaits. I am tired and would put an end to this day. I will pray to God that he is not right about the Normans. If he is, I may just have made the biggest mistake of my life.”

But Leofwine was wrong. It was not the Normans who came.

TWO

10 September, Flamborough Head

The two men stood on the cliffs overlooking the sea, their thick woollen cloaks flapping behind them, buffeted by the strong easterly breeze. Both men were dressed as for war, each equipped with spear and shield, though there would be no fighting for them that day. Rather, their role was to maintain a lonely vigil on this bleak, desolate stretch of Northumbrian coastline, two days’ hard ride to the east of the great city that was Eoforwic.

All around them, seabirds swirled and swooped, diving in and out of the angry waves, hunting for fish. Many more clung to the cliffs, seeking shelter from the stiffening wind. On a clear day, the height of the cliffs would allow the watchmen to see for miles, but with the dark, forbidding clouds on that day, they could see no further than a mile at most. No matter, though, as neither of them believed this day would be any different to the others. Yet again, their lot was to spend the day in mind-numbing tedium, staring out across the waves for signs of invaders. Both knew that, with the approach of autumn and with the weather as unruly as it was, the chances of anyone being foolhardy enough to brave the waters were small to say the least. But watch they must, lest they incur the wrath of Sheriff Osric.

Behind them came the gentle sound of chomping from over by the small clump of trees where they had tethered their horses. The rhythmic sound of them ripping the wispy grass out of the ground before stoically munching it had an almost soporific effect on the two watchers. They had been there since sunrise and it was now well into the afternoon. It was hard to tell exactly, though, as the sun had not once managed to break through the impenetrable layer of thick, dark cloud lay across the sky in every direction.

Saxon Storm: The Huscarl Chronicles Books 1 & 2

Saxon Storm: The Huscarl Chronicles Books 1 & 2